Inspirational Values for Liveable Cities

Mobility, infrastructure, security and environment are key factors in the management of urban areas. But is quality of life in urban areas simply the sum of these key factors or does a liveable city require something more? Making cities liveable is a challenge that concerns all of us. It is an ultimate goal and common to all contemporary and competitive cities around the world. As well as being a basis for their local economy, it is also crucial for the survival of a city. The liveability of cities always is in the mind of planners, designers, city managers as well as citizens, community leaders and mayors. It fits in well with improving a city’s identity and values while, at the same time, making it attractive to its inhabitants, visitors and talents as well as to businesses, developers and investors. A wide variety of conditions determine the liveability of cities. A liveable city provides its residents and visitors with interesting, pleasant and safe public areas, an efficient public transport system, and a healthy and green environment. For a citizen a city needs to provide a sense of belonging and a place and identity to connect to. Cities of today need fresh new approaches to ensure the future liveability and prosperity of their inhabitants and communities.

A sustainable city, an inclusive city – or both?

First of all, liveable cities must ensure the basic needs for food, housing, safety, education, healthcare, mobility, clean air, clean water and waste management. Secondly, cities should encourage the human potential, creativity and talent of their inhabitants. Third, liveability must preserve and restore the natural assets of cities. Cities can no longer afford to damage their natural ecosystems. This is a very complex challenge. A sustainable city is a city that is able to work effectively on energy efficiency, can make the transition to sustainable energy and water management, can reduce or reuse waste products and can reduce the effects of climate change. Making cities liveable and sustainable needs a much broader approach than making a grand design or implementing environmental policies. The values of liveable and sustainable cities are closely related to the values of an inclusive city and a competitive city.

First of all, liveable cities must ensure the basic needs for food, housing, safety, education, healthcare, mobility, clean air, clean water and waste management. Secondly, cities should encourage the human potential, creativity and talent of their inhabitants. Third, liveability must preserve and restore the natural assets of cities. Cities can no longer afford to damage their natural ecosystems. This is a very complex challenge. A sustainable city is a city that is able to work effectively on energy efficiency, can make the transition to sustainable energy and water management, can reduce or reuse waste products and can reduce the effects of climate change. Making cities liveable and sustainable needs a much broader approach than making a grand design or implementing environmental policies. The values of liveable and sustainable cities are closely related to the values of an inclusive city and a competitive city.

An inclusive city gives people a sense of place, of belonging, an identity and the security of social networks. It provides identification and connects pride with its history, community, culture, traditions, heritage and education. Identity, together with attractiveness, is also a major driver for a competitive city. A competitive city is deemed to be successful, prosperous, vital and full of opportunities for businesses, investors and institutions. Combining the values of liveable, sustainable, inclusive and competitive cities is the key success factor for the cities of the future.

Cities have to be flexible

History can help to enhance the liveability in the cities of tomorrow. Throughout the centuries, cities all over the world have been shaped by the availability of agricultural land, energy, raw materials and modes of transport. Throughout history, products were manufactured, goods were traded, taxes were charged and armies were equipped. Cities became increasingly specialized in the manufacture of certain goods, a trade, land defence, government, religion, education and science or culture and in the past decades tourism, sport and media. One of the lessons that can be learnt from the past is that successful towns are not only capable of repeatedly adapting to new functions and identities, but they are also good at combining and including old and new values, functions and identities.

History can help to enhance the liveability in the cities of tomorrow. Throughout the centuries, cities all over the world have been shaped by the availability of agricultural land, energy, raw materials and modes of transport. Throughout history, products were manufactured, goods were traded, taxes were charged and armies were equipped. Cities became increasingly specialized in the manufacture of certain goods, a trade, land defence, government, religion, education and science or culture and in the past decades tourism, sport and media. One of the lessons that can be learnt from the past is that successful towns are not only capable of repeatedly adapting to new functions and identities, but they are also good at combining and including old and new values, functions and identities.

Successful, i.e. sustainable or durable, towns and cities display flexibility. Town and city plans last for a long time and redevelop themselves over decades and centuries to accommodate new functions and to meet new requirements. Changes throughout time and changes in identity and functions are necessary to retain the vitality, competitiveness and liveability of towns and cities. Sometimes drastic measures are called for, such as the construction of the Haussmann boulevards in Paris in the middle of the nineteenth century and the redevelopment of the London Docklands. The transformation of a former landfill for waste disposal on Nanji Island in the Han River and in the middle of Seoul into the five eco-friendly parks in Seoul is another example. Each of these parks has functions and characters for different activities that provide in the needs of the inhabitants of Seoul of all ages.

Towns and cities change

A remarkable example is the redevelopment of the shipbuilding yards and the industrial area of Bilbao into a fashionable city district that houses the Guggenheim museum. The development of extensive parks and the Sun and Moon Pagodas on the shores of the lakes that surround the city of Guilin in the south of China is another example. Both the modern Guggenheim Museum and the traditional pagodas of Guilin are icons of transformation that make two small and historical cities more vital and more attractive.

Towns and cities change. In the twentieth century, they derived their right to exist from the production of goods, a trade or services. These days a creative and recreational economy is required to safeguard the development and prosperity of towns and cities. This is not enough. In the near future, cities will be deemed to be a success when they are capable of coping with climate change and energy transition as well.

Resilient city concepts

Successful and sustainable cities of the near future are searching for solutions at the scale of both the city itself and the surrounding urban region, to seriously tackle the current challenges in the generation of sustainable energy and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. This is no longer just about ‘how can we save (fossil) energy’, but about ‘how can we deploy (sustainable) energy at city level and make it accessible for everyone?’

Successful and sustainable cities of the near future are searching for solutions at the scale of both the city itself and the surrounding urban region, to seriously tackle the current challenges in the generation of sustainable energy and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. This is no longer just about ‘how can we save (fossil) energy’, but about ‘how can we deploy (sustainable) energy at city level and make it accessible for everyone?’

There are many examples. Hammersby Sjöstad is a new district near Stockholm on a regenerated industrial area. The 26.000 residents benefit from local and sustainable energy production. The high density makes light rail a sound alternative to cars and new parks offer an attractive and healthy environment. New town Masdar City in Abu Dhabi is a zero carbon and self-sustaining city. The city will be car-free, energy comes from sustainable sources, waste and waste water will be recycled, and crop fields around the city will provide vegetables for the 40.000 residents. These two of many examples show that sustainability and liveability are closely connected in contemporary planning.

Centuries of experience

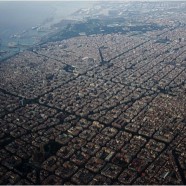

Year 2009 marked the 150th anniversary of Ildefons Cerdà drawing up the expansion plan for Barcelona. This plan comprised a grid of streets and construction blocks that encircled the centre of Barcelona. Cerdà’s city plan was partly inspired by sunlight, fresh air, spacious public areas and public transport for the inhabitants combined with the efficient supply and removal of water, energy, goods and waste. This all seems obvious now, but it was a huge leap forwards compared to the living environment in the old city.

The well thought out city plan made by Cerdà for Barcelona still is successful. It has a prominent place in town planning tradition over the centuries and can be compared with other examples. The city plans of both Jaipur (1731) in Rajasthan, the first planned town in India, and Chandigarh (1953), the capital of the Punjab and Haryana, are, like Cerdà’s plan for Barcelona, well adjusted to natural circumstances and match the social range of thought at that time. In the city concepts of The Garden City Movement (1898) by Ebenezer Howard, Une Cité Industrielle (1918) by Tony Garnier and Ville Contemporaine (1922) by Le Corbusier, the free and unrestricted development of the individual is a central theme.

The city is a brand

In China, the historical water towns that lie in the south of the Yangtze River and along the ancient Grand Canal that connects Yangzhou with Beijing, have combined their efforts in using their historical roots for future development. Cities like Zhouzhuang, Wuzheng and Zhujiajiao have revaluated their cultural heritage as Grand Canal Cities. That unique identity is a brand that binds them together and distinguishes them from other cities. Brighton, one hour by train from London, was branded in the middle of the 19th century as one of the first healthy and liveable cities. The fresh air from the sea in Brighton attracted many inhabitants from London who fled the London smog. Other cities on the coasts or in the mountains, like Davos, soon followed that example.

In China, the historical water towns that lie in the south of the Yangtze River and along the ancient Grand Canal that connects Yangzhou with Beijing, have combined their efforts in using their historical roots for future development. Cities like Zhouzhuang, Wuzheng and Zhujiajiao have revaluated their cultural heritage as Grand Canal Cities. That unique identity is a brand that binds them together and distinguishes them from other cities. Brighton, one hour by train from London, was branded in the middle of the 19th century as one of the first healthy and liveable cities. The fresh air from the sea in Brighton attracted many inhabitants from London who fled the London smog. Other cities on the coasts or in the mountains, like Davos, soon followed that example.

Working on liveable cities requires a constant focus. Barcelona seized the 1992 Olympic games as an opportunity to relocate the harbours and to give the city a seaside character. By doing this, an old identity was discarded and a new identity was taken on. This concept was copied by almost every other city that hosted the Olympic games after Barcelona. London uses the Olympic games of 2012 to regenerate East London to a new sustainable mixed-use city district. Present day city concepts do not stop at city boundaries. Copenhagen in Denmark and Malmö in Sweden have now virtually become a dual city as a result of the new bridge over the Sont (2000) and a joint top quality public transport system.

Charting a course for the future

Making cities liveable or making liveable cities cannot be achieved without the help and the support of the communities and the inhabitants of the cities. They need to be actively involved from the start of every initiative to (re) develop residential areas, infrastructure and to design parks and public spaces. Putting aside the dreams and, sometimes brilliant, ideas of individual citizens and neglecting the often deep rooted and hidden desires of communities is a recipe for unwanted developments. The reality is that most cities are filled with areas that don’t match with the dreams and desires of their inhabitants.

It is an enormous responsibility to plan for the Liveable Cities of the future and opportunity to enhance health and well being in those cities. Charting a course for the future of Liveable Cities starts with talking with their inhabitants, asking for their dreams and listen to their meaningful stories.

The paper ‘Liveable Cities – What does determine quality of life in cities?’ by Martin is written for the Philips Centre for Health and Well-Being in 2010 and presented at the Metropolitan Solutions Seminar at the Hannover Messe on 07 April 2011.

The paper ‘Liveable Cities – What does determine quality of life in cities?’ by Martin is written for the Philips Centre for Health and Well-Being in 2010 and presented at the Metropolitan Solutions Seminar at the Hannover Messe on 07 April 2011.