Next Economy, Next City

The Transition of the Planning Tradition in the Netherlands

The renowned spatial planning tradition in the Netherlands is in the middle of a radical transition. In 2015, proclaimed as the Year of Spatial Planning, the planning community celebrated 50 years of structured national planning, looked back in both admiration and melancholy to the achievements of the Fourth National Spatial Planning Policy (also known as the ’VINEX’) that was launched in 1990. This planning policy very effectively kick-started the development of infrastructure, urban development, urban transformation and public transport in the years that followed. The transition of spatial planning follows the rapid and current changes in our society towards the circular and versatile ‘Next Economy’ and the emerging ‘Next City’ that is liveable, inclusive and cherishes bottom-up initiatives.

The key spatial planning document of the Netherlands, the National Policy Strategy for Infrastructure and Spatial Planning for 2040, has set the transition of spatial planning in motion. This strategy, adopted by parliament in 2012, not only aims to make the Netherlands competitive, accessible, liveable and safe, but also implicates that each level of government has its own responsibilities, delegating more to provincial and local authorities and thus opening the way to dialogue and cooperation in spatial planning decision-making with individuals, businesses, interest groups and community organisations. In short, the Netherlands, and the way we practise spatial planning, is in transition from government to governance. National government policies now are applied more selectively than before, focusing on a limited set of national (and sectorial) interests for which the national government will take responsibility and ensure it achieves results.

The National Policy Strategy for Infrastructure and Spatial Planning embodies the idea that as society and economy change, cities change and the way cities are managed and planned should change as well. This policy strategy stands for the change from top-down planning and government-financed investments towards decision-making in spatial planning that is delegated to the provincial and municipal authorities. This implies that, apart from urban regions around major transport hubs and ports in the metropolitan regions of Rotterdam-The Hague and Amsterdam, the national government no longer dictates, finances or even wants to be involved in the course of urban planning in great detail. The municipal and inter-local coordination and implementation of urbanisation plans will be left to regional and local authorities working independently or in collaboration within provincial frameworks and policies.

2015, The Year of Spatial Planning

In the aftermath of the National Policy Strategy for Infrastructure and Spatial Planning, the planning community realised that an overall and integrated vision, or at least a widely accepted idea in which direction the spatial development of the landscapes and cities in the Netherlands should be heading is missing. A broad alliance of governmental, professional and private knowledge and networking organizations for urban and regional development jointly invested in a full year filled with national and regional public meetings and on-line discussions in which the spatial future of the Netherland was debated with appealing scenarios and provoking agendas for future development. And there is a sense of urgency to this. Just to name a few: due to our rich resources in natural gas and our central position in the trade and transfer of coal and crude oil in Europe, we are way behind the ratified COP21 commitment, agreed on the occasion of the Climate Conference in Paris, to reduce greenhouse gasses and to prevent climate change. The financial crisis of 2008 caused huge losses in the area development and real estate business and affected both the banking sector as well as regional and local governments that were actively involved in location and real estate development. And as the way we work and shop changed rapidly due to the current digital revolution, in some of our cities 20-25% (and raising) of retail and office space is standing empty and wait for redevelopment.

To conclude the Year of Spatial Planning the organisers drafted – under the unifying motto ‘Together We Make the Netherlands’ – the Manifesto for 2040 in which the ambition for the Netherlands is described as ‘the coolest metropolitan area in world that is green, safe, prosperous and circular with a minimum claim on water, soil, natural resources and fossil fuels’. With this eloquent formulated ambition, nobody is harmed or is inclined to disagree. The centrepiece of this manifesto is a set of seven inevitable challenges for 2040 for our common future and five principles for the necessary cooperation among all actors and stakeholders involved to work together on in the living environments of tomorrow’s cities. Those principles address the growing trend in the Netherlands of urban planning as a kind of urban activism: people – after all, ‘what is the city but people?’ – bring an area or a building (back) to life. Local governments assist these place-makers in achieving their aspirations. At present, planners and designers are negotiators between demand and supply and mediators between opportunities and resources. Now public and private partners have insufficient funds for location and real estate development, individual initiatives and small businesses become key to the revival, temporary reuse and subsequent redevelopment of urban areas, finally providing positive energy to a new urban culture.

The inevitable challenges for 2040

The seven challenges as formulated in the Manifesto for 2040 need to be seen in close relation with its underlying strategy to frame the Netherlands as a “Green Metropolis” in order to become more economically competitive and more resilient. The first and foremost of these seven inevitable challenges for 2040 is strengthening the network of cities with public transport. The second and third challenges focus on enabling the transition towards an energy neutral economy and built environment and on enabling every spatial development to contribute to a safe, resilient and robust water system. The other four challenges are bringing agricultural production in balance with its environment, ensuring a healthy environment, anticipating on new technologies in cities, mobility and infrastructures and redeveloping of structurally vacant properties.

The Manifesto for 2040 concluding the Year of Spatial Planning was received with mixed feelings. Most criticasters argued that the on-line discussions and the debates on the many manifestations during the Year of Spatial Planning were casual and lacked depth and that the Manifesto for 2040 poured old wine in new bottles. The manifesto is on the one hand the continuation of coherent planning through the scales, as practised in the Netherlands in the past decades. On the other hand it echoes what urbanist Jan Gehl already is advocating for half a century, that is to make cities lively, liveable, walkable, sustainable and healthy and to stimulate local initiatives. What the Manifesto for 20140 does not provide is a clear idea how the Next Economy will shape the Next City, what drastic measures that will take and how the planning profession should change to accomplish this.

Halfway through 2016, six months after the concluding debate of Year of Spatial Planning, the challenges and principles of the concluding manifesto already seem to have evaporated as a compelling and unifying long term mission about how to deal with present challenges is missing. The merit, however, is that the start of a debate about and the quest for common ground for the economical and decarbonised future and spatial vision on the scale of the Netherlands appear to be back on the table. This is quite an achievement considering that in the last years and at present a neo-liberal government that dismisses a vision for the future as ”an elephant blocking your view” is leading the Netherlands.

‘Let’s Reinvent Planning’

Debate about the state and future of planning and about planning the Netherlands sparked at two international events in Rotterdam, the annual ISOCARP congress and the seventh edition of IABR, which contributed to the Year of Spatial Planning. In October 2015 the City of Rotterdam hosted the plenary part of the 50th anniversary congress of ISOCARP, the International Society of City and Regional Planners. The congress started in twelve different cities in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands with workshops that reflected the ‘Cities Save the World – Let’s Reinvent Planning’ motto of the ISOCARP congress. In Rotterdam the results of these city workshops were brought together and subjected to debate. The results illustrate that as cities are recognised as the engines of national economies, they are the drivers of wealth creation, social development and employment opportunities. Next to this, cities are the choice locations of productive, post-industrial and technological progress, entrepreneurship and creativity. Current preoccupations with climate change, mass migration and energy transition are constantly transforming both the urban landscape and the way that these cities can and need to be managed, planned and prepared for the future.

In his keynote for the ISOCARP Congress, Prof. Maarten Hajer shared his first ideas about the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam (IABR) 2016 ‘The Next Economy’, visualizing the city of the future in the next economy. As the chief curator of this years’ IABR, that was open to the public with debates and exhibitions between April and July 2016, Hajer emphasises that the twenty-first century is undoubtedly the age of the city. “It is where the majority of the world’s population lives, where innovation takes place and where the bulk of economic value is created. However, the infrastructure we need to make the city work is twentieth-century, outdated, overtaxed and we are stuck in the wrong routines planning these cities. We may need a new idea altogether of what the city is and we need to find out which urban strategies successfully combine economic vitality, environmental sustainability, and social inclusiveness in order to make our cities strong, resilient, and agile.”

The Nordic City

The IABR-Atelier Groningen made a brave attempt to answer the chief curators’ statements. In an intensive and interactive process of research by design and exchange with experts and stakeholders, the atelier developed four prospects for the region and the city of Groningen, resulting in one of the highlights of IABR-2016. “This region in the northern part of the Netherlands has seen more than half a century of natural gas extraction, supplying households in the Netherlands and beyond”, atelier master Jandirk Hoekstra explains. “As a result, earthquakes now occur, causing considerable damage from time, and making the people from Groningen to realise that the transition to renewable energy has become inevitable. Both the city and the province of Groningen want to move on and to have largely realized the energy transition by 2035.”

“The IABR–Atelier Groningen has examined the opportunities the transition to renewable energy may bring and specifically whether it can create healthy economic prospects for the city and the region and strengthen the quality of the urban and rural landscape to advance the region’s Next Economy. To our opinion, four interrelated economic clusters stand out: the energy port, bio-based economy, sustainable and safe villages, and the smart energy city. This concept brings all factors together”, Hoekstra concludes, “a whole, strong, complete city surrounded by a wide range of quality-conscious and sustainable green villages, held together by a shared energy ambition and a developing regional energy economy.”

New Coalitions

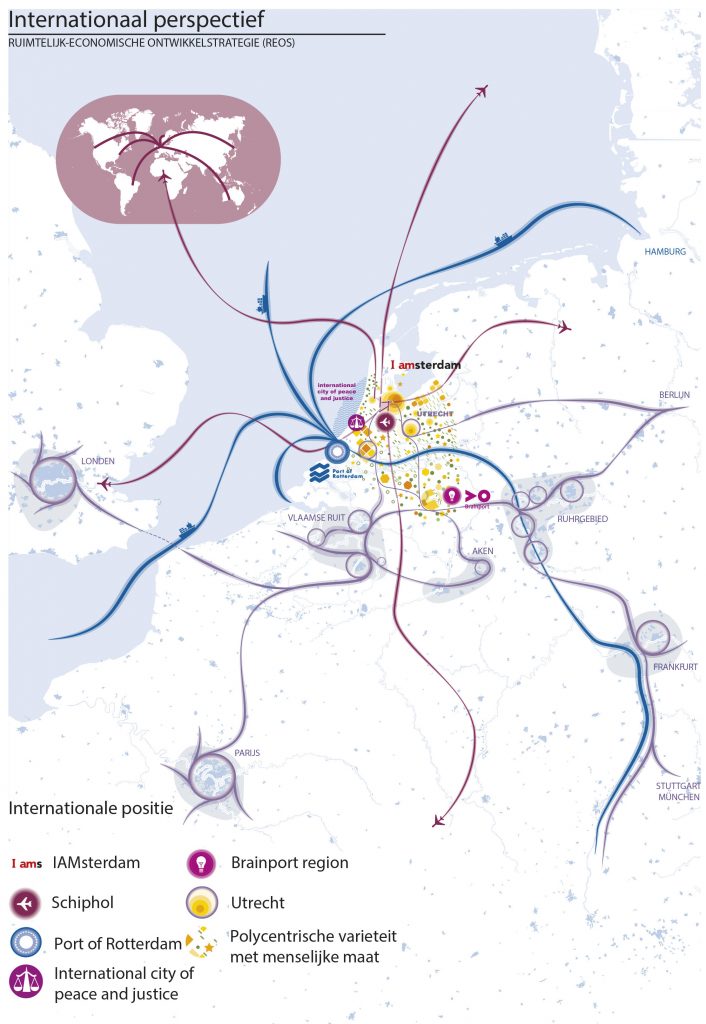

What has become quite clear in the past few years is that in the Netherlands old school and top-down spatial planning is gone for good and that a strategy for a region or a city can only be developed by new coalitions of national, regional and local governments, institutions, businesses and communities. Cautiously and almost reluctantly, the call for a long-term economical and spatial development strategy is answered. In June 2016 no less than 17 ministers, regional economic boards and the mayors of the cities of Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam, Utrecht and Eindhoven agreed to support creating a new strategy that aims at improving the international competitiveness of the network of cities, provides direction towards long-term investments, embraces the next economy, stimulates energy transition and transforms cities into healthy and liveable environments. After all, when “an elephant is blocking your view”, it is wise to change direction.

This article was published in Collage 4/16, Zeitschrift for Planung, Umwelt und Stadtebau, page 9-13. Download this article in PDF here: download-615_next-economy-next-city

References

- Summary of the National Policy Strategy for Infrastructure and Spatial Planning, Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment (2012).

- Curator Statement, Maarten Hajer, IABR-2016-The Next Economy (2015).

- Manifest 2040, Wij Maken Nederland Samen, Wij Maken Nederland (in Dutch, 2015).

- The Nordic City, The Energy Transition for the Next Economy in the City and the Region of Groningen, IABR-2016-The Next Economy (2016).

- Ruimtelijk-Economische OntwikkelStrategie (REOS), Noordelijke Randstad, Zuidelijke Randstad en Brainport Eindhoven, Bestuurlijke intentieverklaring: visie, ambities, opgaven en aanpak, (in Dutch, 2016).

- Websites: isocarp.org, www.iabr.nl/en, www.wijmakennederland.nl.